Asset Characteristics in High-Yield Debt

High-Yield Lending and Asset Volatility: Understanding the Risk-Return Tradeoff

High-yield commercial real estate lending, particularly mezzanine debt, often appears attractive due to high coupon rates and enhanced equity returns. However, beneath the surface lies an important and underappreciated factor: the quality and volatility of the underlying asset. This analysis explores how mezzanine returns respond to changes in asset-level volatility and challenges the assumption that a fixed coupon offers consistent value across projects.

Rather than treat all mezzanine loans as equal, this study reveals that their performance varies significantly depending on how lenders view and price risk. It introduces two perspectives: one where lenders ignore asset volatility (a myopic view), and one where lenders price the risk appropriately (a risk-neutral view).

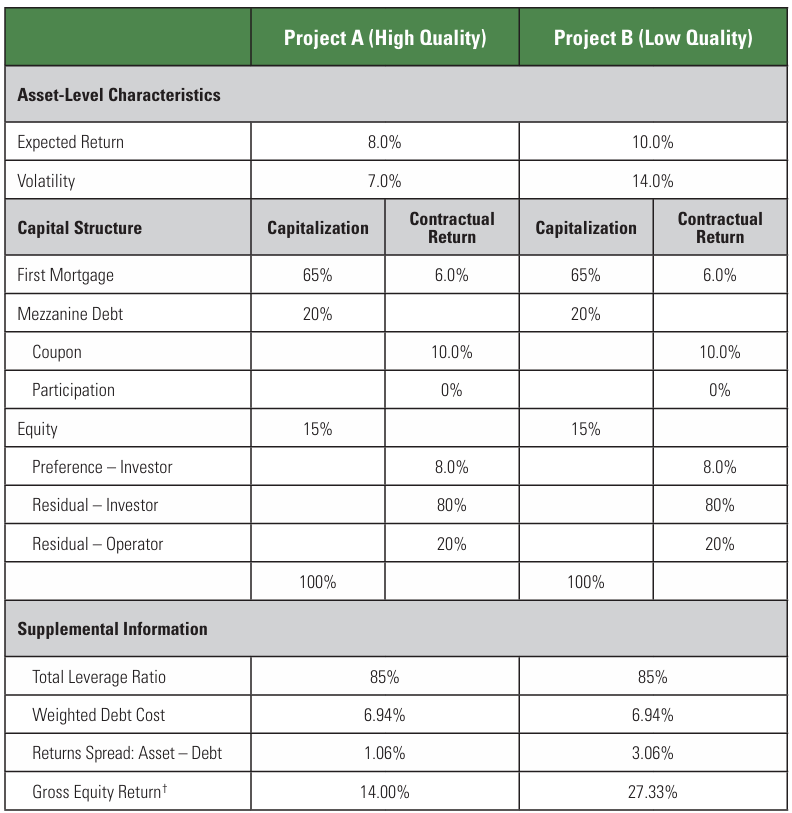

Exhibit 1: Initial Setup – Two Projects, Same Structure, Different Risk

This exhibit introduces two hypothetical projects:

- Project A is a high-quality, low-volatility asset

- Project B is a lower-quality, higher-volatility asset

Both projects use identical capital structures: 65 percent senior debt, 20 percent mezzanine financing, and 15 percent equity. Each mezzanine loan carries a 10 percent fixed coupon and no profit participation.

Although both structures appear the same on paper, Project B promises higher asset-level returns because of its riskier nature. The question is whether that extra return compensates the mezzanine lender for the additional risk.

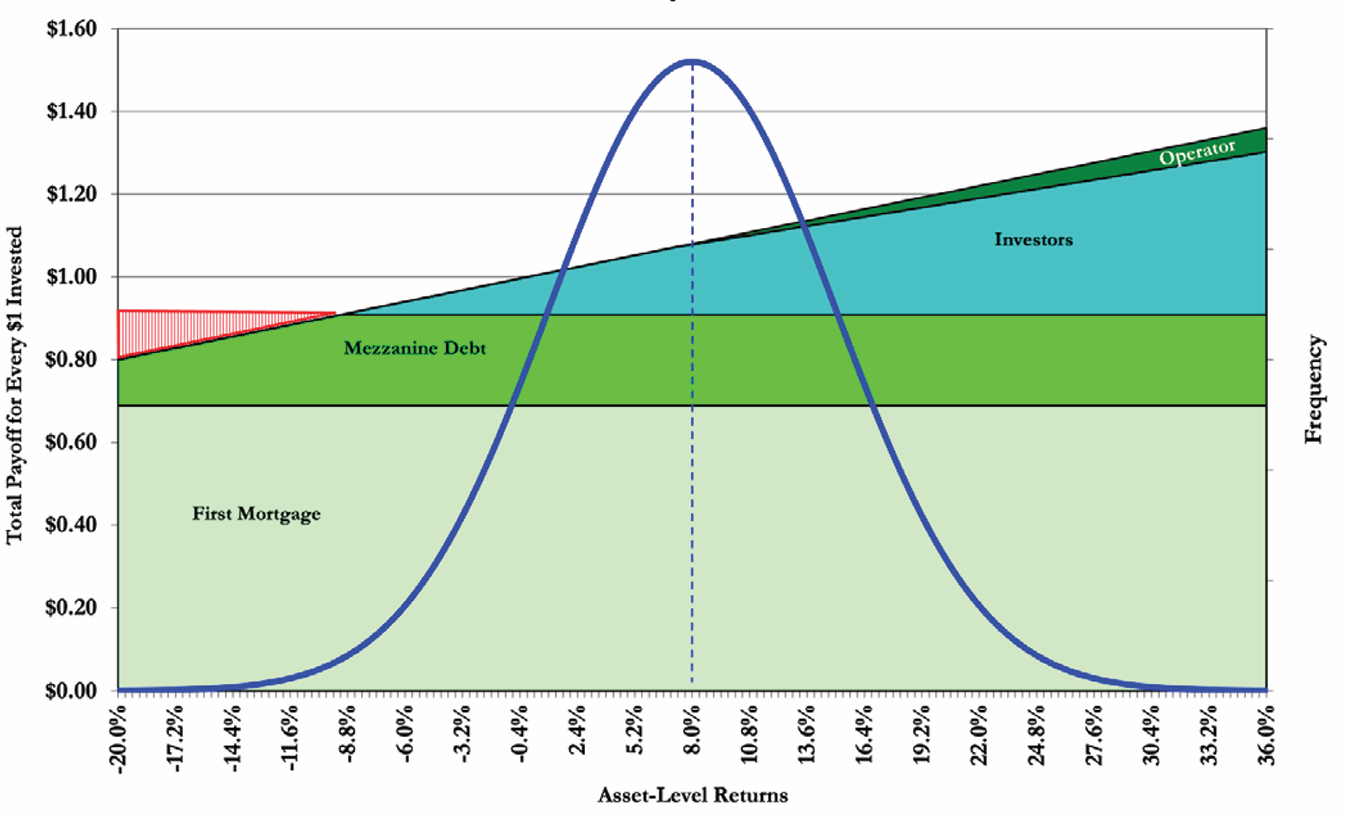

Exhibit 2: Project A – Payoff Structure for a Stable Asset

This exhibit visualizes how returns are distributed across the capital stack when Project A performs across a range of outcomes.

The bell curve shows the likelihood of various asset returns. The shaded areas reflect who gets paid first: senior debt, then mezzanine, then equity. In most cases, the mezzanine lender is fully repaid, as downside risk is limited due to low asset volatility.

In a stable project, the mezzanine lender is relatively well protected, and expected returns align closely with the fixed coupon.

Exhibit 3: Project B – Payoff Structure for a Riskier Asset

This exhibit applies the same visual logic to Project B, the more volatile asset.

Even though the average asset return is higher, the downside risk is far greater. Losses to the mezzanine lender are more frequent and severe. Since the lender’s upside is capped at the 10 percent coupon, the increased volatility mostly harms rather than helps.

Comparing Exhibits 2 and 3 shows that higher asset volatility, even with greater average returns, results in worse outcomes for the mezzanine lender. What looks like a high-yield opportunity may in fact expose the lender to uncompensated risk.

Exhibit 4: Mezzanine Returns Across Outcomes in Project B

To better understand the risk exposure from Exhibit 3, this chart isolates the mezzanine position in Project B. It shows how much of the mezzanine loan is repaid across different asset return outcomes.

There is a wide band of potential losses for the mezzanine lender. Although full repayment occurs most of the time, there is a meaningful chance of partial or complete loss. The risk-return profile is asymmetric, the downside is real, while the upside is fixed.

Exhibit 5: Comparing Risk and Return Across the Capital Stack

This exhibit quantifies the outcomes observed visually in the earlier charts. It shows the expected return and volatility for each part of the capital stack in both projects.

Senior debt returns are nearly identical in both projects since defaults are rare. Mezzanine debt in Project A earns a return close to the coupon with very low volatility. In contrast, mezzanine debt in Project B earns a much lower return with much higher volatility.

Even when coupon rates are identical, returns to mezzanine lenders depend heavily on asset quality. Treating different projects the same leads to significantly worse risk-adjusted outcomes.

Exhibit 6: What Happens When Lenders Ignore Risk

To generalize the insight from the two projects, this exhibit examines a full range of asset volatilities under the assumption that mezzanine lenders keep coupon yields fixed, regardless of risk.

The blue line shows how asset-level expected returns increase with volatility. However, the green curves show that expected mezzanine returns decline as volatility rises.

As asset volatility increases, downside losses become more frequent and severe. Since mezzanine lenders only earn a fixed coupon but can still suffer large losses, their returns decline as volatility grows.

Exhibit 7: Mezzanine Return Volatility Also Increases

While Exhibit 6 shows declining expected returns, this chart adds another layer by plotting how the volatility of mezzanine returns changes with asset volatility.

The return to mezzanine lenders becomes not only lower but also more uncertain. This further highlights the flaw in treating all mezzanine loans as equal. Without adjusting pricing, lenders become risk-seeking without intending to be.

Exhibit 8: Adjusting Coupon to Maintain Consistent Expected Returns

Now, the focus shifts to the risk-neutral view. If lenders were to price risk properly, they would raise the coupon yield on mezzanine loans as asset volatility increases.

This chart shows the required coupon yields needed to maintain the same expected return across a range of asset volatilities.

For high-risk assets, the required coupon could exceed 30 percent, which may be impractical or unaffordable for borrowers. This highlights the limits of adjusting fixed interest rates alone to manage risk.

Exhibit 9: Using Participation Features Instead of High Coupons

As an alternative to higher fixed coupons, lenders can add profit-sharing mechanisms. This exhibit shows the participation rates needed to achieve the same expected return as in lower-risk projects.

The required participation rates rise with asset volatility but stay within more manageable ranges than extreme coupon hikes.

This mechanism allows lenders to share in the upside of riskier projects, improving return potential without overburdening borrowers. Still, the volatility of returns remains high, meaning that some risk is simply inherent in lending against volatile assets.

SUMMARY

This analysis challenges the notion that mezzanine debt can be priced uniformly across different asset types. When lenders ignore asset-level volatility, they expose themselves to lower expected returns and higher uncertainty. A risk-neutral approach that adjusts pricing or includes upside sharing provides more balanced returns, but also requires thoughtful structuring.

Across the nine exhibits, we move from a simple two-asset comparison to a broader continuum of risks, showing both the consequences of mispricing and the tools available to correct it. Ultimately, asset volatility matters. Mezzanine lenders who fail to account for it may be taking on more risk than they realize, and not getting paid for it.

These analyses are intended solely for academic purposes. No warranty or representation is made with regard to their accuracy.